BIRDIES AND GOOGIES

A Hummingbird Update & The Mastermind Behind the Googie Design Aesthetic: Helen Liu Fong

“Being a commercial architect was the most fun job in the world if you were lucky enough to have been one in the '50s and '60s, the field’s most innovative period.” - Helen Liu Fong

If you enjoy this post, hit the ♥️ button, leave a comment, or restack. Those actions help others discover my work. Thank you!

Hiya Friends,

I know some of you are mainly here for the hummingbird report, so let’s get right to it. We have BABIES! (*SQUEAL*)! Today I saw a teeny tiny beak sticking out of the nest and I tried to take a video while keeping a safe distance. That video didn’t turn out great, but I did capture the video below of Mama bird feeding her chicks. I’m hoping to see some little heads pop out soon. Stay tuned!

GOOGIE WONDERLAND(*sounds like Boogie, but with a G*)

Perhaps because I’m a native Angeleno*, I’ve always been drawn to and enamored with Googie architecture. Special thanks to Gayla Gray and her wonderful Stack SoNovelicious, Books & Reading & More Books for sharing the link to the recent piece in the New York Times about the effort to save these beloved mid-century structures from destruction here in LA.

Popular in the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, Googie—a space-age style of architecture designed to lure drivers out of their cars and into a booth for a burger — featured whimsical flourishes like slanted/swooped roofs, glass facades, saw-tooth pennant signs, neon, and bright pops of color. If you’ve ever watched The Jetsons cartoon, pretty much every building in the title sequence could be classified as a Googie.

So what the heck is Googie and where does the name come from? Well, in 1949, a Los Angeles businessman named Mortimer C. Burton hired the famous mid-century architect John Lautner to design a coffeeshop on the corner of Sunset Blvd and Crescent Heights Boulevard. When the time came to name the joint, Mortimer went with “Googie,” the nickname his family lovingly called his wife, Lillian.

If you’re wondering how the name of a coffee shop came to represent an entire style of architecture, the credit goes to an uppity Yale professor/architectural writer named Douglas Haskell. Apparently, Haskell and the architectural photographer Julius Schulman, were tooling around Los Angeles and Haskell spotted Googie’s Coffee Shop. “Stop the car!,” he shouted. “This is Googie architecture.”

He then proceeded to denigrate the buildings in an article for House and Home Magazine in 1952. Haskell’s big beef with Googie, as expressed in his article, was that the structures lacked refinement, and existed purely to draw attention to the business, essentially screaming, "Look at me, come in, and spend your money!" Good thing Haskell didn’t live long enough to see a pop-up ad on the internet. It would’ve melted his brain.

When I moved back to Los Angeles in the late 90s, I rented an apartment in West Hollywood (the neighborhood where I lived as a kid, and home to the first Googie’s restaurant). Next, I purchased a 1965 Ford Fairlane from an auto pawn shop, and, on the rare day that the car wasn’t overheating on the side of the road, I drove around to admire the Googie architectural gems still standing. My guidebook at the time was Googie: Fifties Coffeeshop Architecture (1986) by the architect and writer, Alan Hess.

In an interview with Smithsonian Magazine in 2012, Hess explained Googie’s allure in post-war America.

“I really feel that Googie made the future accessible to everyone,” Hess says. As he explains it, Googie was an unpretentious aesthetic meant to appeal to the average, middle-class American: ”One of the key things about Googie architecture was that it wasn’t custom houses for wealthy people — it was for coffee shops, gas stations, car washes, banks… the average buildings of everyday life that people of that period used and lived in. And it brought that spirit of the modern age to their daily lives.”

HELEN LIU FONG: THE GOOGIE MASTERMIND

In the Who’s Who directory of mid-century design, John Lautner, Richard Neutra, Ray and Charles Eames, and Frank Lloyd Wright are household names, but how many people know that the person responsible for establishing the Googie aesthetic was a woman named Helen Liu Fong? Not many I bet.

The daughter of Chinese immigrants, Helen Liu Fong was born in Los Angeles on January 14, 1927. She and her four siblings grew up in Chinatown and helped their folks run the family laundry business. At age 12, a guidance counselor asked Fong which career she’d like to pursue. Young Helen, in 1939(!!!), said she wanted to be architect. Fong’s guidance counselor, who I imagine did a spit take into his coffee mug, asked Fong what she’d do if she had that job. “I don’t know, build houses?” Fong said.

It’s likely Helen was told that achieving her goal would be tricky if not impossible, especially in an era when barely any women, and even fewer Asian Americans worked in the field of architecture. Meanwhile, Chinese immigrants had long been victims of racist attitudes and discrimination in the United States. Their ability to travel to and from the country had been restricted by the passage of The Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. That ban wasn’t repealed until 1943, four years after Fong’s meeting with her guidance counselor.

I find it remarkable that at twelve-years-old, Fong had such a clear vision of her future. Did any of you have your career figured out at age 12? I sure didn’t. In the 6th grade, I remember wandering around the playground on “Career Day” dressed like Chef Boyardee because I loved me a jaunty hat. Spoiler Alert: I did not become a professional chef.

Fortunately for Fong, her father wanted his daughter to be self reliant. He encouraged her to get an education. Post-high school, she attended UCLA for a couple of years, then transferred to UC Berkeley, earning a degree in city planning in 1949.

It will probably surprise no one that, after graduating at 22, Fong received zero job offers to work as an architect. She finally secured a position with the Chinese-American architect Eugene Kinn Choy. His firm designed Chinatown’s Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association and Carthay Bank. Alas, Choy did not hire Fong on as an architect associate, but rather as his assistant.

“At that time, I think it was perfectly acceptable to dismiss women’s credentials,” says, Steven Wong, curator of the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery and former interim director at the Chinese American Museum. “Eugene Choy—who was also struggling with race as an architect in a field that was pretty homogeneously white—hired Helen as a secretary. I think that’s really telling. [He was] supportive, but at the same time, she should have been so much more than a secretary.”

SHE RAN THE SHOW AT ARMET & DAVIS

Two years later, Fong walked down the hall and poked her head in at Armet & Davis — an up-and-coming architectural firm. They hired her on as a junior draftsperson in 1951.

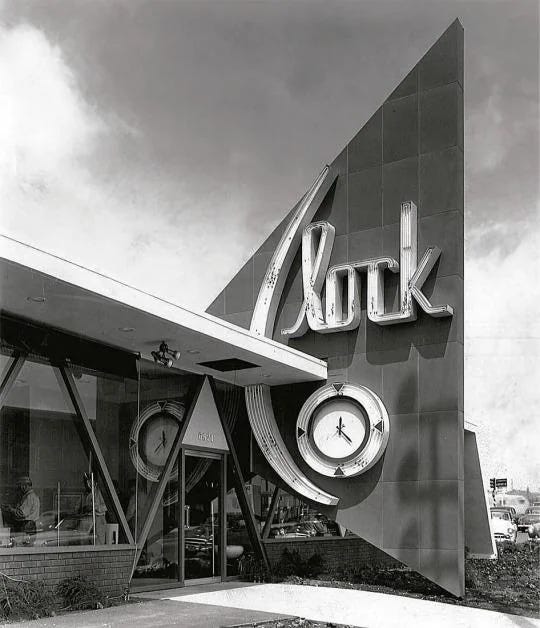

Shortly thereafter, Armet & Davis secured their first Googie commission—The Clock Restaurant in Westchester. The timing (HAR!) proved auspicious for Fong. Almost immediately, Fong’s unique vision and fanciful approach set her apart from the rest of the mostly-male team, and she began to establish Googie’s signature style. For starters, Fong, a native Angeleno, knew that the locals spent most of their day in a car. In order to attract a driver’s attention, businesses needed bold design, bright colors like red and yellow (she hated blues and greens), and clusters of plants so one could enjoy the outdoors whilst sitting indoors.

“Helen was one of the people who helped to shape the whole aesthetic of Googie, especially with relation to interiors,” says Alan Hess.

And though Fong is often credited with overseeing the interiors, her touches were evident in the exteriors as well. “Clock’s restaurant in Westchester was the first roadside coffee shop in our trademark Armet & Davis style, with a see-through front that made it seem like there were no walls,” Fong told Los Angeles Magazine in a 2000 profile.

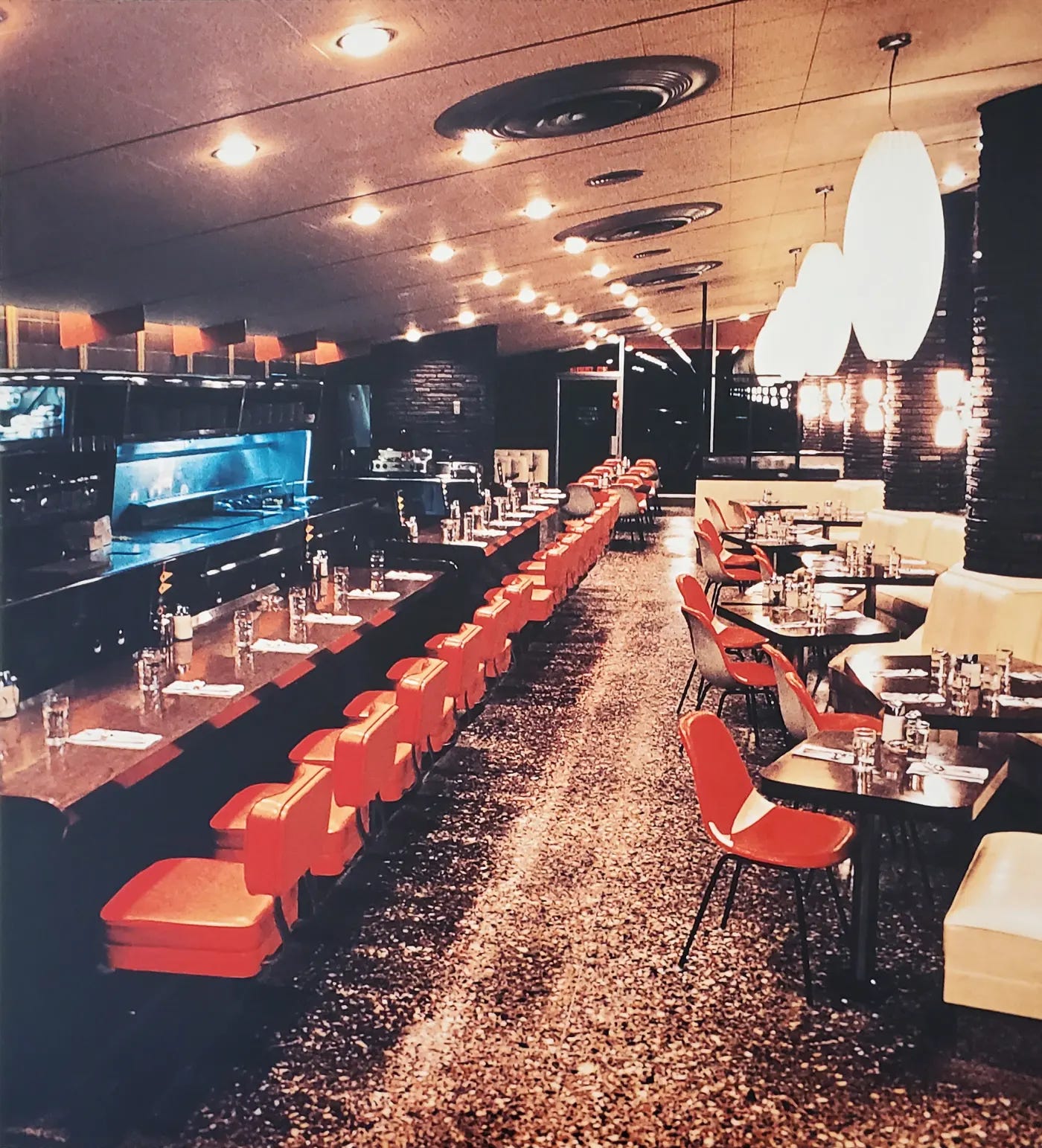

Soon Armet & Davis were one of the most sought-after firms for Googie structures. In 1955, the team worked on the very first Norm’s on South Figueroa, a popular Los Angeles coffee shop named after the founder, Norm Roybark. “We suspended big Herman Miller bubble lights from the high ceiling above the front row seats to help create a cocoon effect,” Fong explained. “In interior architecture, you want people to walk in and experience things in small focuses. I would lay out the seating precisely to suit my scale to make things a little more intimate.”

Branching out from eateries, Fong trained her keen eye and imagination on the Holiday Bowl, a Japanese-owned bowling alley located on Crenshaw boulevard. She outfitted the bowling alley with all the coolest mid-century accessories, including George Nelson bubble lamps and Eames chairs covered in orange vinyl. In the groovy cocktail lounge, The Sakiba Room, Fong installed a 3-D map of Japan crafted from “refrigeration cork and lined with gold foil edges,” to celebrate the proprietors’ culture.

I was lucky enough to bowl there once and grab a cocktail in the lounge with an old flame. I remember sitting at the bar when that fellow told me I had nice hands. A few years later, that guy and the bowling alley would be history. In 2003, The Holiday Bowl was converted into a Walgreens and a Starbucks. *sigh*

According to one of Fong’s former colleagues, the architect Victor Newlove who joined the team in 1963, Helen Liu Fong did more than just dream up playful decor; she ran the show at the firm. “She was an excellent businesswoman. She taught me how to be a businessperson. Louis Armet and Alden Davis, they were horrible businessmen, I’m sorry. If it were up to them, we would’ve been broke.”

Fong also didn’t suffer fools and impressed upon her colleagues the importance of a peaceful work environment. Newlove found that out the hard way his first week on the job. “I came into the office on Monday. I was there at my desk, and I was smoking in those days, and I was whistling. All of a sudden, I feel a hand on my shoulder and I look up and it’s Helen Fong. She says, ‘We don’t whistle while we work.’ . . . She was the boss.”

PANN’S RESTAURANT BUILT IN 1958

Sadly, many Googie structures have been torn down over the years. A few still exist though and one of the most gorgeous examples is Pann’s Restaurant. Located right near Los Angeles International Airport, this family-owned restaurant is pure Helen Liu Fong. Of course she’d only been credited with designing the interiors. It wasn’t until after she’d retired in the 1970s that she told her friend, the architectural historian, John English, “I actually designed Pann's, you know.”

That design work included the booths, chairs, countertops, barstools, lighting, doorknobs, tiling, silverware, the glaze on the dishes, employee uniforms, and the look of the menu. She even hired artists to create artwork for the walls. Right before the restaurant was set to open, Fong did a walk-through and hated that the wall behind the counter was all white, so she took out a bottle of red nail polish and painted each tile red. It stayed that way for decades.

A couple of months ago, I met my brother for breakfast at Pann’s and the place was packed. I’m sure its location near the airport is a boon for business, but it’s really Helen Liu Fong’s design that draws you in and makes you want to linger. The bright red booths, exposed lava rock, groovy hanging lights, and the sun pouring in through the glass lifts the mood. What I’ve always loved about Googie structures is the vibrance, the whimsy, and the joy they exude. Turns out that’s exactly what Helen Liu Fong had intended for her designs.

“We all knew that commercial architecture would come and go based on the forces of commerce. It wasn’t our function to think in the long term. If we could make restaurants appealing, make you feel good when you’re in them, we’d done our job,” Fong said.

These days, designers tend to favor a bland and muted palette. I find it all so oppressively humdrum, snoozy, and insidious. I want orange banquettes. I want bubble lights. I want neon signs. But they don’t want us to have color. David Speed wrote about this in the Creative Rebels Substack. “At some point, white Western upper-class society deemed itself ‘above’ the love of colour.” It’s just like Haskell crapping on Googie because the coffee shop had the gall to attract his attention.

This war on color must be stopped. What we really need right now, with the state of our nation in complete chaos, is more color, not less, and to patron the businesses that aren’t afraid to buck norms and rebel against tyranny.

Helen Liu Fong did that with her bold and audacious designs in the 1950s and ‘60s. She created a visual language for the city and built transportive meeting spaces that were accessible to everyone. She broke barriers and paved the road for many women and people of color who came after her. “She never became a licensed architect, and yet she probably was responsible for more architecture than most architects,” said Victor Newlove. She also never made partner at Armet & Davis, but Victor Newlove, the person who credited her with teaching him everything he knew about the business, managed to get his name on the door. Go figure.

Fong died in 2005. Over the past few years, she’s gained more recognition as a true pioneer of mid-century design and honored for her contribution to the profession. It doesn’t make up for the fact that Louis Armet and Eldon Davis never promoted her to partner even when she single-handedly kept the business afloat, but hopefully more people know her name today. For readers who don’t live in Los Angeles, next time you visit, be sure to pop into Pann’s to marvel at the wonder and beauty of Helen Liu Fong’s vision. You’ll be glad you did.

Okay, that’s a wrap for today. Thanks for being here. I know this was a long post today, but I felt like Helen Liu Fong deserved to be celebrated.

Wonderful!

Oh no I didn’t know Hollywood Bowl got torn down! I left in 98 and have only been back a few times and I hardly recognize L.A. anymore. This was a fascinating story. Even furniture and lamps of the mid century era were cool and quite popular in the 80’s. It’s kind of a bummer that it’s all been cheaply recreated at stores like Walmart. PS we get hummers too, love them!