STAY PLAYFUL, MY FRIENDS

Life Lessons from a 103-Year-Old Toy Designer, Creativity = Longevity, Ode to Grandpa Monroe

"I think when you do creative work, you stimulate your brain and that helps keep your body healthy." - Eddy Goldfarb, Toy Designer Extraordinaire

Hiya Friends!

Hope you’re enjoying a bit of fall weather in your part of the world. Here in Los Angeles, I’m thrilled to report that I’ve worn a sweater at least three times. For a couple of weeks, the temp hovered in the high 60s/low 70s and there was a glorious breeze a blowin’. I tend to avoid weather reports because my meditation app advises me to live in the moment. And yet, despite my best efforts to stay in a Zen zone, some naysayer inevitably comes along to warn me that the sun is about to swallow Los Angeles. “What a gorgeous day,” I’ll say to a random passerby. And 90% of the time, the response will be something like: “Yeah, but it’s supposed to 115 degrees tomorrow.”

Perhaps this compulsion to fixate on the worst possible outcome is a leftover trait from our Neanderthal days when danger lurked around every corner. But isn’t it time we gave ourselves a break from Chicken Little-ing for an hour or so to enjoy some sweater weather or that first sip of coffee/tea/functional mushroom brew in the morning? Who’s with me?

Okay. Pep talk over. Back to the beautiful weather. Jared and I made the most of those perfect days by taking brisk walks in the late afternoon. Our dog, Noodle, is 18. He can still walk and enjoys a short stroll around the block, but a 2-mile hike is much too far for him to handle. So we popped Noodle in a dog stroller (we borrowed it from a neighbor, but yes, we’ve become those people), and he sat upright like a furry tank commander, keeping an eye out for enemies. All he needs is a tiny steel helmet to complete the look. ⬇️

Based on the fact that Noodle seems content and never tries to jump out of the moving vehicle, we’ve determined that these strolls bring him as much joy as they bring us.

STAY PLAYFUL, MY FRIENDS

And since we’re on the topic of joy, if you’re of a certain age, chances are you grew up playing with wind-up toys. I certainly did. My dad and his father, Monroe, collected them.

When we were kids, my brother and I spent countless hours pitting these wind-up toys against each other. Fire-breathing Godzilla battled Chattering Teeth. Pecking Chicken faced off with Marching Green Robot. Whichever toy careened off the table first was the loser. If my brother’s toy teetered too close to the table’s edge, he’d knock over my toy and shout, “I win!” Classic big brother move.

All of these memories came rushing back when I watched the mini-documentary posted above about Eddy Goldfarb—the inventor of 800 toys including the iconic chattering teeth (!!). The documentary was shot when Eddie was 98-years-old. He’s 103-years-old now.

I love Eddie’s story so much. He’s a true inspiration and a testament to how being playful and creative is the real key to longevity. In the film, Eddie describes himself as optimistic. “I annoy people with my optimism,” he admits. Oh, I know the feeling, Eddie. I’m an optimist too and there’s been times when I’ve tried to lure someone off the ledge only to have them look at me like I have rolled oats for brains. But it’s okay, I’m used to it. So is Eddie. In addition to his optimistic outlook, Eddie credits his creative work for keeping his brain and body healthy. Turns out, scientific studies have proven he’s onto something.

CREATIVITY = LONGEVITY

One art activity a month increases life expectancy by 10 years, according to Susan Magsamen, founder and director of the International Arts + Mind Lab, Center for Applied Neuroaesthetics at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Studies conducted found that even folks who attended museums, concerts, or galleries a few times a year lived longer than their peers.

So if you needed an excuse to bust out your sketchbook or to take a day off to stare at some art, here it is!

ODE TO GRANDPA MONROE

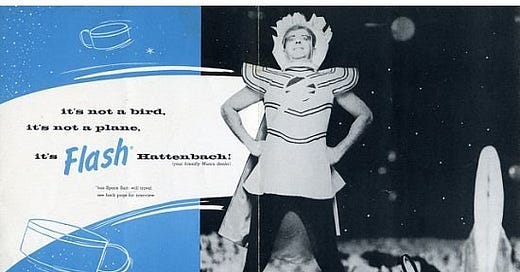

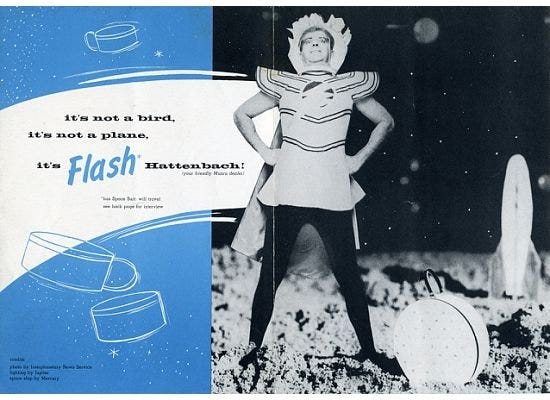

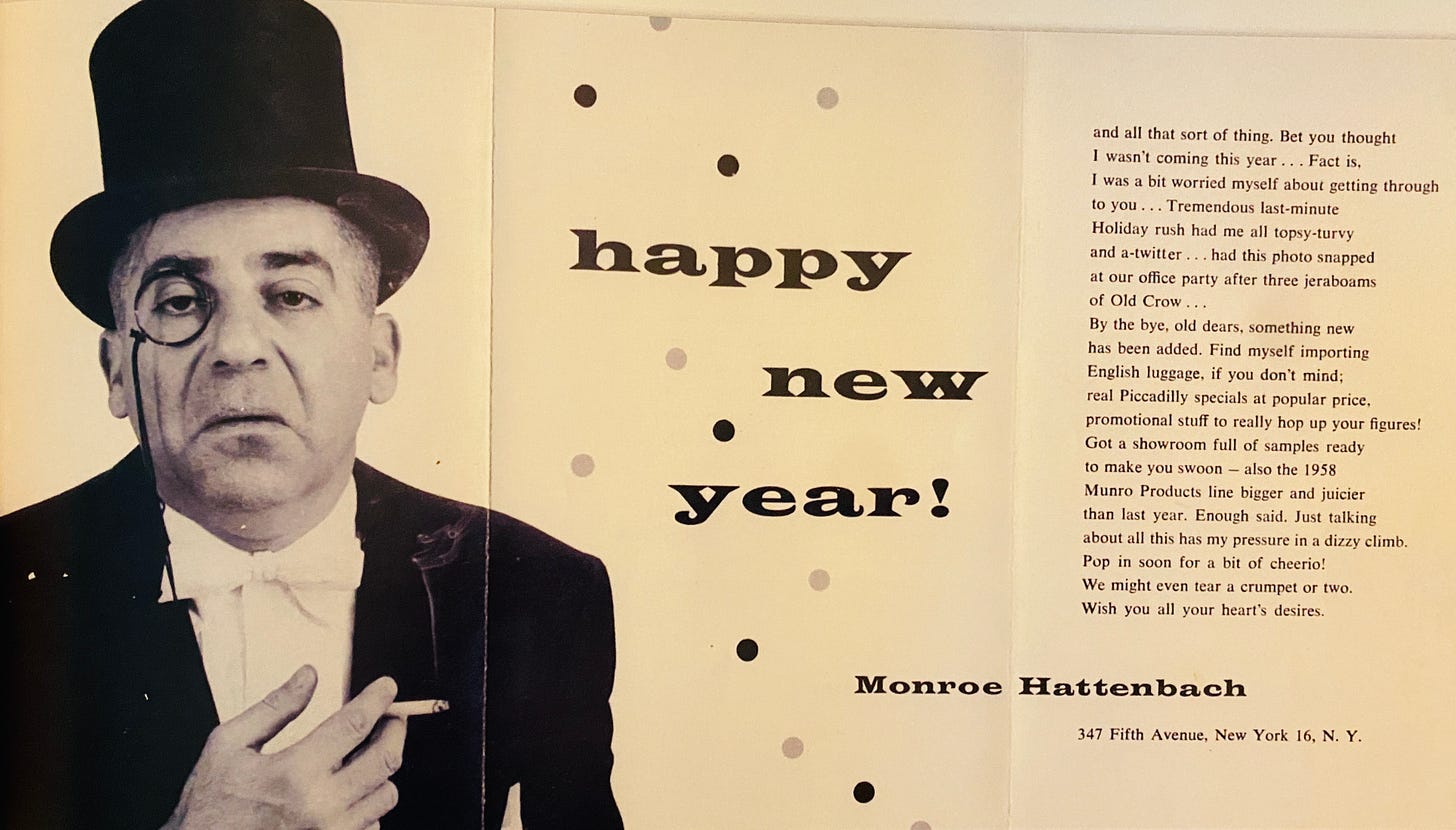

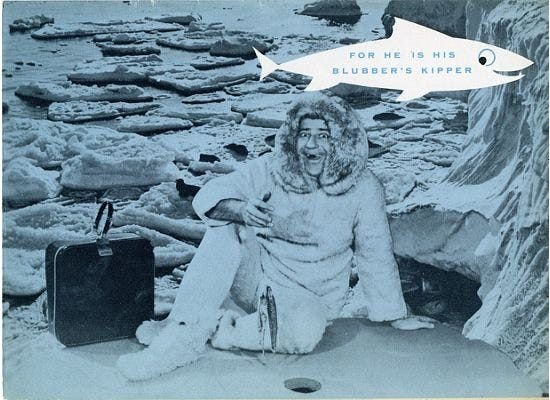

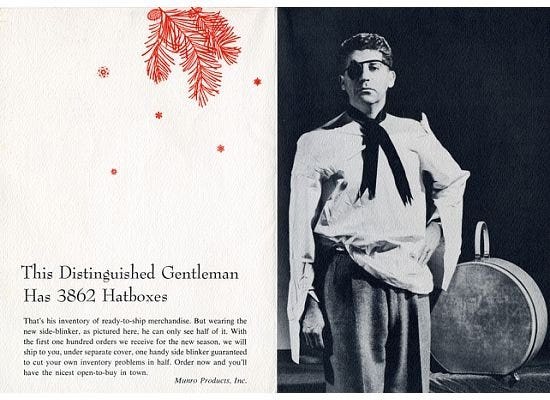

Like Eddy Goldfarb, my paternal grandfather, Monroe, was a fun-loving guy and a real gas. In the 1950s, he ran a company that sold women’s travel cases and hat boxes. Each year he’d send out a custom greeting card to all of his clients (see images above). I think his silliness and joie de vivre kept him going until it was eventually snuffed out by overwhelming loss. I wrote a piece about him that I’m going to share here because the only way to truly capture his essence is to show him in action. You’ll see in the essay below, I refer to Grandpa’s third wife as M2 so as not to be sued for libel.

DISAPPEARING INK

A waiter in a shrunken dinner jacket zipped past our booth, carting a lobster platter that left a briny scent in the air. My paternal grandfather, Monroe, sat across from me in the almost empty dining room of The Captain’s Table, a seafood restaurant on La Cienega Boulevard in LA. That night he looked dapper as always, dressed in a periwinkle sport coat and starched shirt. At 6’1 with a snowy head of hair, Grandpa Monroe held the honor of “tallest Hattenbach” in our diminutive clan.

“$50 for a lobster?” he said, his dark eyes widened in shock. “What are they? Crusted in rubies?”

Chris, my nine-year-old brother, tossed back his head of auburn curls and laughed, exposing gapped front teeth.

“Oh, Monroe.” Grandpa’s third wife, M2 rolled her eyes. An uptight and attractive blond with a bell-shaped coiffure, M2 had nary a wrinkle on her clothes or her face—thanks to a little nip and tuck—and looked like the type who might slit your throat with one pointy pink fingernail.

The year was 1977, and my brother and I had joined my grandfather and his wife for dinner. Grandpa Monroe and M2 lived in Florida and had made a pit stop in Los Angeles on their way to lounge by the ocean in San Diego. At the time, my mother, brother, and I lived in a rent-controlled apartment in West Hollywood, California. My parents had been divorced since I was two and my musician father, Tony—Grandpa Monroe’s son — was spending most of his time on the east coast avoiding his parental duties.

“The Pritikin Meal looks great,” Grandpa said. “We should all get that.” He snapped his menu closed to signal the waiter.

I straightened up in my chair and placed a napkin over my Swiss Miss-style dress. At age seven, I wasn’t the most adventurous eater and I scanned the menu for something recognizable like fish sticks. At the bottom of the page under “Low Calorie/Low Salt,” I spotted the Pritikin Meal. This “special” consisted of salad, boiled chicken breast, tomato slices, cottage cheese, and sorbet for dessert. An incongruous choice at a restaurant famous for lobster and clam chowder, but as an observant youth, I noted the Pritikin meal’s low price—three-courses for $20. I didn’t mind having to eat unsalted chicken, but sorbet depressed me. It didn’t qualify as a real dessert. I would lobby for chocolate cake later.

My grandfather, a life-long entrepreneur, had tried his luck with a string of unsuccessful business ventures, including manufacturing men’s shaving kits and a women’s accessory line of suitcases and hatboxes. His first marriage to my father’s mother was short lived. His second wife, Nadine, a woman I never met but whom my mom referred to as “the love of Monroe’s life,” died an untimely death from cancer. Nadine and Monroe had a son together named Jamie, and Monroe also adopted Nadine’s older son, Marc from a previous marriage. After he married the wealthy widow, M2 in the 1960s, she bankrolled their life of comfort in a high-rise condo in Coconut Grove, Florida. M2 had two daughters from her previous marriage and several grandkids living in Florida.

Back at The Captain’s Table, Chris and I picked at our tasteless chicken and sat enraptured as Grandpa Monroe entertained us with jokes that he told in a put-on Yiddish accent. We laughed until our cheeks ached.

The waiter dropped off dessert and plunked down the check. Grandpa Monroe lifted a corner of the bill, peered at the total, and clutched his heart.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

He shook his head, took a deep breath, and blotted away imaginary flop sweat with his napkin. “We just bought the restaurant!” His eyelids flapped in exaggerated concern. “Chris, grab that whale painting off the wall, we own it now.”

My brother jumped out of his seat, snorting with laughter, and tried to lift the heavy wooden frame off the wall.

Grandpa stuffed a saltshaker in his pocket and raised a finger to his lips.

This became my grandfather’s longest running gag, performed at the end of every single meal. A legendary prankster, he lived to entertain and kept a well-stocked arsenal of props in his home office. Bookshelves were lined with wind-up toys that squirted water in your eye and little cartoon figures that shouted expletives. Hidden fart cushions lay dormant under every couch pillow.

His dedication to silliness knew no bounds though, on a few rare occasions, I caught a glimpse of his serious side. A Dartmouth-educated intellectual and voracious reader, he enjoyed listening to classical music, completing the New York Times crossword puzzle, and loathed improper grammar. When I was around eight or nine, he sent me a letter. Enclosed, I found my most recent correspondence to him with the spelling and grammar errors circled in red ink. He included a stern note that simply said, “Dearest, Hilary. Use a dictionary. Love, Grandpa Hatt.”

I stared at the marked-up page and felt a rush of hurt, embarrassment, and shame. Grandpa Monroe’s notes were usually chatty updates detailing his recent travels or a funny anecdote. Afterwards, I proofread every letter to him with a vengeance.

Years later, in my twenties, my paternal grandma would tell me that Grandpa Monroe had been a cold father. “He believed that children should be seen and not heard. He ignored your poor father and barely gave him any attention. He treated Nadine’s son more like a son than his own.” And while Grandpa was very warm to me and Chris, it helped explain how my own father had failed to receive the good parenting memo.

Following the seafood dinner antics, Grandpa Monroe handed Chris and me each a check for $10. “Buy yourselves something special,” he said with a wink.

Chris suggested that we pool our money and spend it all at the joke shop at the Farmer’s Market on 3rd and Fairfax. Both in awe and afraid of my older brother—a seasoned troublemaker who’d accidentally set our garage on fire by playing with matches—I quickly agreed to his scheme.

Chris wandered the aisles of the joke shop, collecting inane items to torture friends and family; disembodied bloody rubber thumbs, packs of gum that snapped the fingers of unsuspecting patsies, toffees that tasted like a salt lick, plastic vomit, and fake dog poop. I gravitated towards a bottle of disappearing ink. Disappearing ink is just that. When squirted on a white surface, the color is bright blue but after a minute or two, it disappears. Following this shopping spree, I morphed into kid version of a pushy perfume salesperson. I doused everyone I knew with disappearing ink and, when the blue liquid vanished into thin air, felt vindicated that, as I had always believed, magic was real.

Several months later, Chris and I flew to the Sunshine State to visit our dad and the bulk of our extended family. One day, Pops had to work so he dropped us off at Grandpa Monroe’s Coconut Grove condo. Located in a looming glass tower, the structure resembled a high-rise hotel with valets who opened car doors and asked, “Who are you here to see today?”

We crossed the swampy driveway into the air-conditioned lobby and rode the brass elevator up to the 7th floor. M2 opened the door and pressed her pink lips together into a tight smile. “Hello, Children.” She leaned in and made a puckering sound near our cheeks though refrained from skin contact. “If you need the bathroom, use Grandpa’s down the hall. You are not to step foot in the living room.” Her powdery perfume lingered as she led us into the spotless apartment, over to Grandpa’s office, and shut the door.

I translated my step-grandmother’s orders to stay sequestered in a tiny square of the condo as a punishment, as if Chris and I were feral beasts that needed to be contained. Though I had no proof, I convinced my seven-year-old self that when M2’s kin came over, they had free rein of the place. I still hadn’t met them, presumably because we were Monroe’s low-rent spawn. As I plopped down on my grandfather’s couch and detonated a hidden fart cushion, I pictured M2’s three spoiled granddaughters dressed in fur coats and Jordache jeans living the high life. I suspected that they used any bathroom that they wanted and ate chocolate ice cream cones on the white couch in the forbidden living room. I worked myself into a jealous frenzy over this perceived inequity.

For the most part, I was a well-behaved child and avoided misdeeds, but something about M2’s icy attitude pushed me over the edge. Shortly after we arrived, I hatched a plan. While Grandpa was on the phone, I waved my brother out of the office and tiptoed into the museum-worthy living room. There were no footprints in the plush white carpet. No butt dents on the puffy cream-colored side chairs or matching sofa. Not a single fingerprint or smudge on the glass coffee table.

Stifling chortles, I squirted disappearing ink all over the white couch while Chris cheered me on. The bright blue liquid hit the surface and made a zig-zagging print resembling a Rorschach test. I enjoyed a moment of sheer euphoria, knowing I’d done something a little wicked, but as the stain bled into the fabric, a sick feeling rose in my chest. What if it didn’t disappear this time? The package said to test it out on a tiny corner of fabric first and I hadn’t done that. If it stained that couch, M2 might impale me with one of her fingernails. If she didn’t kill me, I would absolutely be grounded for life. I figured that Grandpa, the perennial joker, would get a kick out of the gag, but if I ruined his couch, it would be a lot worse than a few spelling errors in a letter.

The ink appeared to soak deeper into the couch.

“Let’s go back to Grandpa’s office,” I whispered to Chris.

“You’re going to be so busted if that doesn’t come out,” Chris said, ever the supportive big brother.

We started to tiptoe out of the room as M2 rounded the corner and caught us in her all-white sanctuary.

“What are you doing in here?” she barked. “You know, you’re not allowed in this room. And what in God’s name is all over the couch?” Her wrinkle-free face didn’t shift but her eyes seemed to transform into blue fireballs.

“It’s disappearing ink!” I blurted. “It’s going to disappear any minute.” I stared at that splotch, willing it to vanish.

She crouched down to inspect the cushion, blocking my view. For all I knew, the blotch had expanded and was enveloping the entire couch.

“What’s going on in here?” Grandpa bounded into the room in his cheery way.

“Your grandchildren are trying to destroy my couch!” she fumed.

My heart ticked like a game show timer about to run out.

Grandpa stifled a laugh. It was a relief to see him smile.

“I don’t see anything,” he said.

I craned my neck around him. The mark had fully disappeared, thankfully. I let out an audible exhale.

M2 shook her head and stomped off.

Grandpa waved us back into his office, shut the door, and said in a grave tone, “You know you really shouldn’t upset your Grandmother like that. She might not want you to come here anymore and I would hate that.”

I knew what he meant. It was M2’s apartment. I didn’t fully comprehend all the details of their arrangement at the time, but I later learned that M2 paid most of the bills, hence Grandpa’s tendency to always order the cheapest thing on the menu. If M2 decided we weren’t welcome, there wasn’t anything Grandpa could do about it. I was on my best behavior the rest of the trip.

Grandpa and I remained close over the years and yet, I still never met M2’s family. My brother went to college in Florida and got to know them a bit, but I was all the way in California, annexed from this mythical extended family, and I continued to vilify them.

In my teens, I once made a call to the Coconut Grove apartment. M2’s eldest granddaughter answered the phone and said, “Hattenbach Residence.”

“Can I please speak to my grandpa?” I said.

“He’s my grandpa too,” she said, defensively.

And I remember thinking, “You’re not a Hattenbach.”

During my sophomore year of college, I attended a 40th birthday in Miami for my Uncle Jamie, Grandpa Monroe’s youngest biological son from his marriage to the love-of-his-life, Nadine. Jamie had been diagnosed with terminal brain cancer.

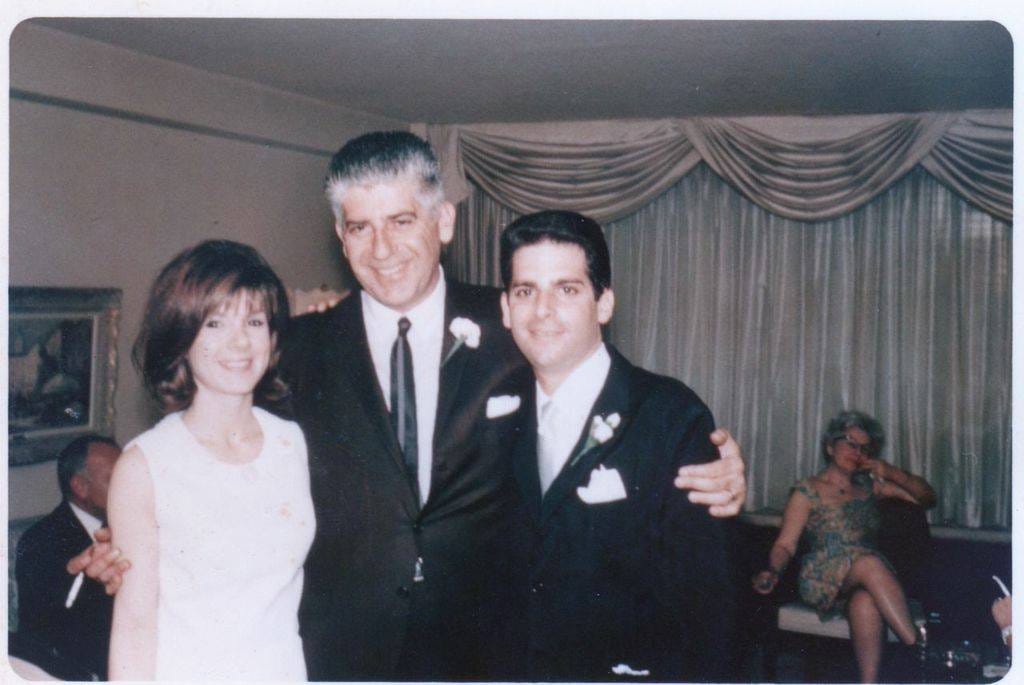

Colorful balloons and streamers hung above a giant birthday cake, but the mood was somber. I have a photo from the event where my father is sporting a deep dark tan and a button-down shirt that’s way too tight. A pack of Benson and Hedges cigarettes are stuffed in his front pocket and he has his arm around my Uncle Jamie—a sweet, low-key guy with big ears. Jamie’s face appears ashen and bloated in the photo, dark circles surround his eyes, and his hair has thinned. Grandpa stands on the other side of my dad, smiling wide, but the signature sparkle in his eyes is gone, replaced by sadness. His arm is around my father. M2, dressed in all-white, has drifted in from the side like a photo bomber, smiling with one hand clutching a glass of wine and the other hanging by her side. I suppose she might have felt like an outsider in that intimate moment, standing next to Grandpa with his two sons from other marriages, but at the time, I judged her inability to place an arm around her husband and show warmth.

Uncle Jamie died later that year. Within five years, Monroe’s adopted son, Marc, lost his battle with cancer and passed away. That left my father, Tony, the chain-smoking, sun-worshipping, timbales-playing offspring as the last son standing. Monroe had closer relationships with Jamie and Marc, perhaps because they were the children of his favorite wife, but my pops was the most like Monroe in many ways. A theatrical performer who spoke seven languages, Pops loved to tell jokes and shared his father’s attraction to silly tchotchkes. Pops was also no stranger to failed business ventures.

Grandpa and my pops grew closer after the death of Jamie and Marc, meeting for lunch once a week. Then my father was diagnosed with esophageal cancer. He died a year later. Just before my father’s funeral, a perfunctory death announcement ran in the Miami Herald. I read it with horror, noting the multiple errors, including the spelling of our last name. My cellphone rang. It was Grandpa Monroe and he was livid.

“What the hell is with that announcement in the Herald? Did you see how they spelled Hattenbach? With a K? And they didn’t list his next of kin. It’s appalling.”

This was the ultimate affront—misspellings and bad grammar in his own son’s obituary. I assured Grandpa that I was on the case and that I was paying for longer version that would contain all the correct information.

Grandpa kept it together at the funeral, receiving condolences, and not shedding a tear. I was a blubbering mess. I heard that M2’s family was in attendance but the whole event was such a blur, I don’t have any memory of it.

On my next visit to Florida, Grandpa, at 92 years old, was in failing health though no specific diagnosis had been reached. Chris and I went to visit him at the Coconut Grove condo. He was in his office, wrapped in a white blanket on his easy chair like a chrysalis. The shades were drawn, and the room was lit only by one dull floor lamp. More frail than I’d ever seen him, his white hair was neatly combed back and the color was drained from his face. M2 stood behind him and rested a hand on the back of his chair.

“Look, Monroe. The kids are here,” she said, as if hoping our visit might give him a sudden burst of energy.

I tried to tell him some funny stories, but he had run out of joy.

“I no longer believe in God,” he said, out of nowhere. “I can’t believe in a God who would take all three of my sons and let me live.”

It broke my heart to see his spirit so crushed.

Shortly after that visit, back in Los Angeles, I had an intensely vivid dream. In it, the phone rang, and when I answered, my father said, “Hilary?”

“Pops? Where are you?” I asked.

He said, “Hang on, Grandpa wants to say hello.”

“Grandpa’s there?”

The line went silent for a minute, as if Pops was waiting for his father to pick up another celestial extension.

“He can’t come to the phone right now. He’s too far away but he’ll be here soon,” Pops said.

Grandpa Monroe died a week later at 93.

M2 asked me to speak at Grandpa’s funeral. I was touched by the gesture, seeing it as her way of acknowledging the special bond Grandpa and I shared.

I was the only grandchild to eulogize Monroe that day. I kept it light and told stories like the famous, “We just bought the restaurant” gag and another one about a trip to Disneyland where Grandpa sat behind my brother on the Matterhorn and said, ‘If I throw up on your shirt, you can change it later.” The mourners laughed at Grandpa’s hilarity. I’m certain that’s how he would’ve preferred to be remembered.

Following the funeral, at the high-rise in Coconut Grove, we noshed on deli platters and I finally met M2’s three granddaughters and grandsons. On that day, I found out that Grandpa Monroe was the only grandfather M2’s granddaughters had ever known. They loved him just as I did. We swapped funny stories and, much to my surprise, they were never allowed in the white living room either. They were lovely, down-to-earth people who’d suffered their own share of losses, not the spoiled rich kids I’d always imagined. As we sat around reminiscing, I knew Grandpa would’ve been so happy to see all his grandkids sharing a laugh.

I wish I could say this brought us all closer, but we’ve since lost touch. And I’ll admit, from time to time, I’m still a bit sore at M2 for never offering Chris and me a memento to remember our grandfather by. It would’ve been nice to inherit some photos, a wind-up toy, or a fart cushion. Like my grandfather and my father before me, I love tchotchkes. M2’s grandkids, however, were forever redeemed in my eyes that day and all the resentments I’d harbored towards them as a kid have long faded away just like that blotch of disappearing ink.

Okay, that’s a wrap for today! ⤵️⤵️

Beautiful story Hilary. You have so much of his humor and positivity. Loved seeing these cards too, and of course Noodle in the carriage!

I loved the film about Eddy Goldfarb. The chattering teeth and Kerplunk! Those toys are just superb, and it's great that he had the imagination to think of the ideas plus the skill to make them. Totally prepared to believe that an optimistic outlook, enthusiasm and keeping as fit as possible all make for a better and possibly longer life.

Great essay about your grandfather. It's so brave to write about family and you do it with such wisdom. I can just see little Hilary spilling that ink on step-grandma's sofa! 😱